|

A

child in the 1980's, I lived, breathed, and loved movies.

Every genre, every type…from boyhood fantasies of aliens

and adventurers courtesy of Spielberg, to somber tales

of axe-wielding fathers and war-torn battlefields courtesy

of Kubrick. (I saw FULL METAL JACKET three times when

it came out; I was a pretty intense 13-year-old.)

But

however great my experiences then - this was, after

all, the decade of Indiana Jones, Rambo, halfway

decent Star Wars sequels, Back to the Future,

Ghostbusters, and a pre-nippled Batman -

I think what excited me most, whenever stepping beneath

that local town center theater marquee, was the chance

to see the latest round of movie posters.

An

important clarification: when I say "movie poster",

I'm not referring to the photo-touched, photoshopped,

photodigital photocrap that's become the norm these

days, slick and stylish though some may be. I'm talking

about real movie posters - the big, artful, sometimes

cheesy, often delightful product of some guy who actually

sat down behind a drafting table and put a sharpened

pencil to paper.

That's

pencil, I said now. Not pixel.

It's

probably the toughest art to master for any illustrator.

It's not just about getting the actors' likenesses right;

it's about conveying the best and most enticing things

a movie going experience can offer -- it's soul,

if you will -- even if that sounds a bit inflated

when so many films out there are such soulless enterprises.

Most

poster artists rarely get the chance to see the very

films they're slaving over prior to finishing their

work. Commissions often come at the very last minute,

with deadlines fast approaching. (A rather inexcusable

crime on the studios' part, when one considers the inordinate

amount of time they waste gestating their projects.)

It's

a tough job, and poster artists are a rare breed.

|

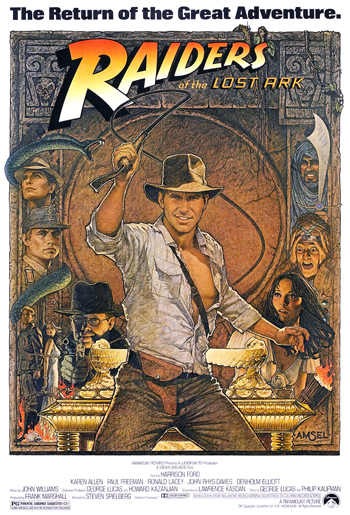

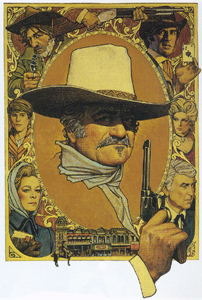

Have

whip, will travel: Poster for RAIDERS' 1982

re-release, featuring Amsel's trademark montage

illustration style.

|

For

me, "masters" like Bob Peak, Drew Struzan and Roger

Kastel deserve to be held in the same regard as classic

illustrators like Norman Rockwell, Maxfield Parrish

and N.C. Wyeth. Why? Because at their best, their work

didn't just convey the highlights of a movie coming

soon to a theater near you, but rather they built upon

the anticipation, the promise and excitement of what

(hopefully) was in store…hinting just enough to whet

our appetites, while not spoiling things by giving too

much away.

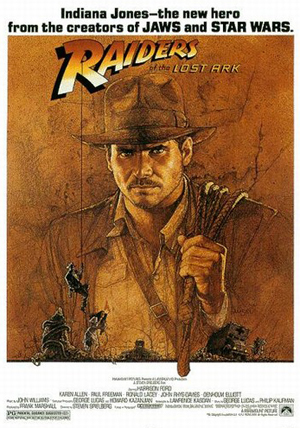

Toggle

through some of the pages on my site and it will come

as no surprise that RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK is my favorite

film of all time. But it also has my favorite movie

poster of all time.

Look

at this poster at right, used for the film's re-release

in 1982. I challenge anyone to so perfectly capture

a film's spirit within a single drawn image.

It's

not just that the actors' likenesses are good; here,

they take on a larger than life quality -- epic, heroic,

even cartoonish, but all in the most wonderful, high-spirited

way imaginable. Like the film itself, this poster evokes

the grand, stylish, and cheesy fun of 30's and 40's

adventure serials, while executed with far more sophistication

and visual panache.

Simply

put, this poster is the movie, and I've been

a fan of both ever since.

Of

all the American illustrators of the 20th Century, there

are two whose work I have admired the most. The first

is Joseph Christian Leyendecker. The second is Richard

Amsel.

These

men lived and worked decades apart, and their experiences

were far removed from each other. Leyendecker, born

in Germany in 1874, trained in Chicago and Paris, and

produced literally hundreds of works of enormous influence

and popularity, most notably his covers for The Saturday

Evening Post and his advertisements for "The

Arrow Collar Man".

Before

Rockwell (with whom the artist had both a close friendship

and career rivalry), Leyendecker was the

great American illustrator, and his career spanned over

half a century.

Amsel's

career lasted fifteen, a life cut short by the AIDS

epidemic. He was 37 years old.

Yet

I don't think it's outlandish to make a comparison between

these two men. To say that they were extremely gifted

is all too obvious; both Leyendecker and Amsel were

something of art prodigies, and both began their respective

careers at a very young age. In Leyendecker's case,

it is said that his talent, while studying at the Chicago

Art Institute, was already so sophisticated that his

art instructors didn't know what was left to teach him.

(Or perhaps Leyendecker felt they had too little to

contribute.) In similar fashion, Amsel's career took

off while he was still a mere student at the Philadelphia

College of Art. When 20th Century Fox sponsored a nationwide

poster contest for their big budgeted Barbara Streisand

vehicle, HELLO DOLLY, it was Amsel's design that took

the prize; the artist was then a ripe old age of 22.

On

a personal level, perhaps it's because both Leyendecker

and Amsel strike me as enigmas that I find them so intriguing.

Little is known (or at least has been made public) about

their private lives, and, however great their success

during their respective careers, neither name is quickly

recognized by the public … an especially peculiar, bittersweet

fact when compared to the enduring popularity of their

work.

Of

Leyendecker, this we do know: he was gay, had a lifelong

partnership with Charles Beach, a man who served as

the artist's model, caregiver, and business "agent"

of sorts. Leyendecker remained intensely private about

their relationship, and grew increasingly reclusive

after the death of his brother, Frank, in 1924.

(Frank

was a gifted artist in his own right, though he reportedly

often struggled with living in the shadow of Joseph's

towering success.)

I

mention Leyendecker's sexuality not to incongruously

dwell on the topic -- the question of how much an artist

need be revealed when discussing his art is another

matter entirely -- but to put his life in historical

perspective. Leyendecker kept his personal life private

because, understandably, social attitudes of his day

dictated he do so. But so extreme was his need for secrecy

that only a handful of photographs of the man still

exist; Beach, apparently acting on Leyendecker's instructions,

burned many of them upon the artist's death in 1951,

along with virtually all of their personal writings.

In

fact, most of what we know today about Leyedecker's

life has been from Norman Rockwell, whose early work

was so influenced by the elder artist's that Rockwell

devoted an entire chapter to him in his autobiography.

As

for Amsel's private life, I feel no need, nor find it

in good taste, to besmirch it in any way simply because

the man had AIDS. Thousands did then. Millions do now.

The virus' only relevance for my discussion here is

that it robbed us of a superlative talent, and all the

glorious, wonderful work that could have been.

|

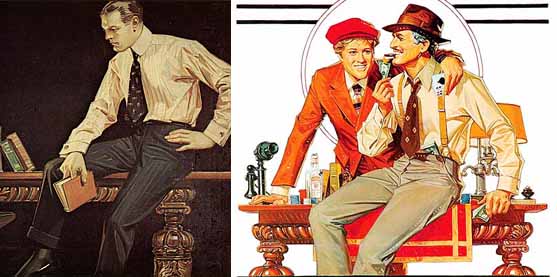

For

THE STING's movie poster (detail right, 1973),

Amsel's design paid homage to the painting syle

of J.C. Leyendecker, and evoked both Leyendecker's

"Arrow Collar Man" (left) and his beloved

Saturday Evening Post covers. Leyendecker's

technique is extremely difficult for even skilled

painters to emulate; Amsel was in his mid twenties

when he did it.

|

The

dearth of available information on Amsel, the man, always

seemed odd to me, as his career in the seventies and

eighties was relatively recent. Surprising, too, is

the almost complete lack of material on Amsel in the

two places I had most expected to find them: the Motion

Picture Academy Library in Beverly Hills, and the Philadelphia

College of Art, where Amsel studied.

His

obituary in Variety seemed cruelly brief, even

fleeting. It opens, "…illustrator for numerous Hollywood

film print campaigns as well as portrait artist for

many TV Guide covers, died Nov. 17 in New York of pneumonia,

it has been learned."

No

tributes, no thoughtful eulogies or tender reflections.

Of Amsel's family, it merely stated that he left behind

his parents, a brother and a sister.

Why

does this affect me so? What is it about Amsel's work

that I find so remarkable? Why should I wonder so much

about the man, and look back on his career with such

poignance, even tenderness?

BIOGRAPHY

Richard

Amsel was born in Philadelphia on December 4, 1947.

He attended the Philadelphia College of Art, and, thanks

in no small part to his winning HELLO DOLLY illustration,

quickly found enormous popularity within New York's

art scene.

The

key to his success, beyond raw talent, was the unique

quality of his work and illustrative style. Amsel could

perfectly evoke period nostalgia (his posters for THE

STING and westerns such as McCABE AND MRS. MILLER come

to mind), while also producing something timeless and

iconic, perfectly befitting both something old and something

new. And however different his approach from one assignment

to the other, all would bear his instantly recognizable

stamp. Not to mention a damn cool signature:

"Amsel's

work usually pays affectionate tribute to the past,"

one critic stated. "His style, however, is timeless

and his attractive use of warm, glowing colors adds

an even greater 'modernity' to his evocations of times

and styles gone by."

Amsel

himself said, "I'm interested in uncovering relationships

between the past and the present, and in discovering

how things have changed and grown. I don't see any point

in copying the past, but I think the elements of the

past can be taken to another realm." Such was the case

with an early commission from RCA Victor, who asked

the artist to create new artwork for their remastered

recordings of Helen O'Connell, Maurice Chelalier, and

Benny Goodman.

Amsel's

illustrations then caught the attention of a young singer/songwriter

named Barry Manilow, who at the time was working with

a newly emerging entertainer in cabaret clubs and piano

bars. Manilow introduced the two, and it was quickly

decided that Amsel should do the cover of her first

Atlantic Records album.

You

could say it was a sure Bette.

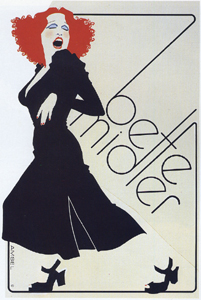

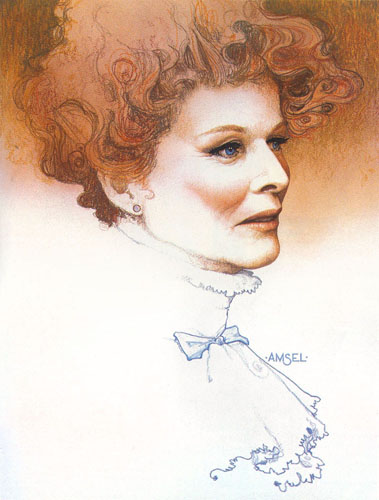

The

artist's cover for Bette

Midler's The Divine Miss M presented the 5'2"

entertainer as a sort of natural-born icon, and one

would be hard pressed to argue that Amsel's subject

didn't deserve such treatment.

More

album covers soon followed, along with a series of magazine

ads for designer Oleg

Cassini, but it's Amsel's portraits of the fire-haired

diva that remain the most popular.

|

Bette

Midler

(2)

1973

Acrylic and ink on board

30 x 23 1/2 in.

|

Bette

Midler -- Clams on the Half Shell

(2)

Oil on canvas

29 7/8 x 30 in. |

Amsel

continued illustrating movie posters, and for some of

the most important and popular

films of the 1970's: THE CHAMP, CHINATOWN, JULIA, THE

LAST PICTURE SHOW,

THE LAST TYCOON, THE LIFE AND TIMES OF JUDGE ROY BEAN,

McCABE & MRS. MILLER, THE MUPPET MOVIE, MURDER ON THE

ORIENT EXPRESS, NASHVILLE, PAPILLON, THE SHOOTIST, and

THE STING among them. (The latter's

poster design paid homage to none other than Leyendecker.)

Though

brief, Amsel's career was certainly prolific. By the

decade's end his movie posters alone matched or exceeded

the creative output of many of his contemporaries. Yet

Richard Amsel was

far more than just a movie poster artist.

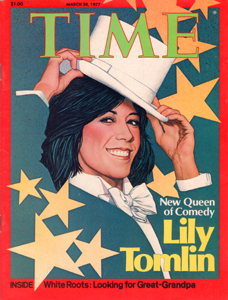

|

Talk about a killer deadline! Amsel's cover art

for TIME, featuring Lily Tomlin, was created in

only two or three days. It is now part of the

Smithsonian

Institution's permanent

collection.

|

His

work graced the cover of TIME -- a portrait of

comedienne Lily Tomlin, now housed in the permanent

collection at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington

D.C. In keeping with the magazine's stringent deadlines,

Amsel's illustration was created in only two or three

days.

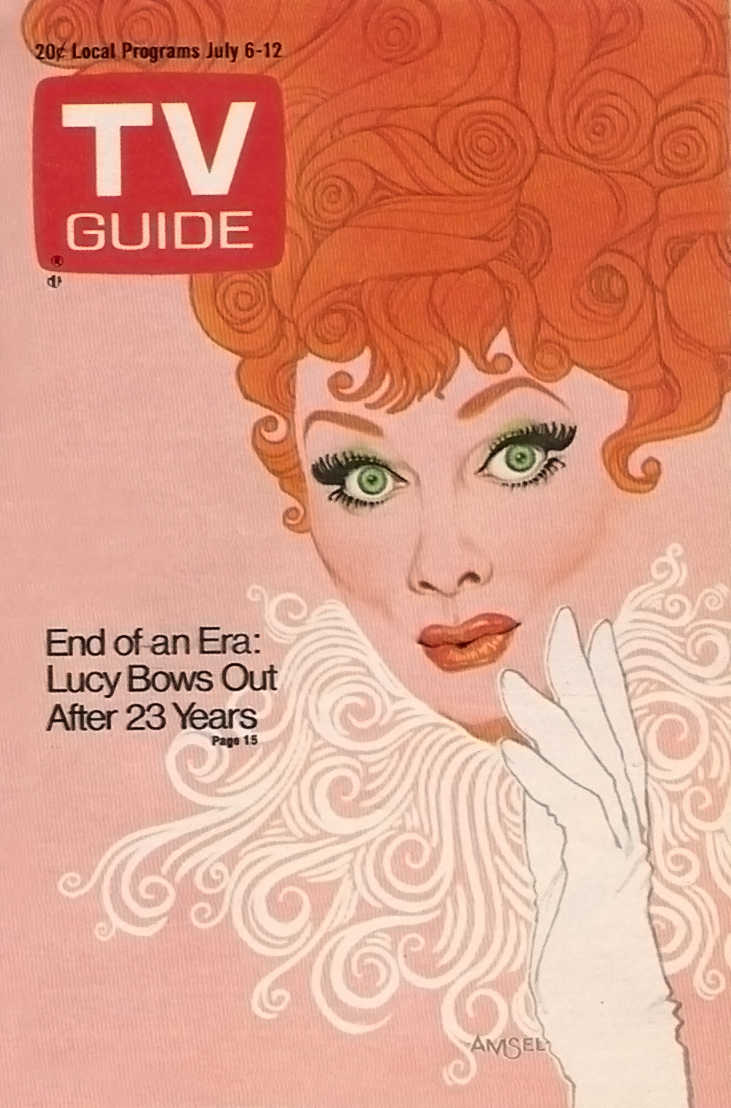

LONG

ASSOCIATION WITH TV GUIDE

In

1972, TV Guide commissioned him to do a cover

featuring the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, coinciding

with a telefilm about their love affair. Thus began

Amsel's thirteen year association with the entertainment

magazine, resulting in 37 published covers -- a

record Amsel holds to this day. (Not unlike Leyendecker's

record for The Saturday Evening Post.)

The

"Amsel covers", now prized collector's items,

feature portraits of such figures as Mary Tyler Moore,

John Travolta, Elvis Presley, Ingrid Bergman, Johnny

Carson, Tom Selleck, Nancy Reagan, Frank Sinatra, Princess

Grace and Katherine Hepburn. Particularly notable issues

include Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh for GONE WITH THE

WIND's television debut, the wedding of Prince Charles

and Lady Diana, and Richard Chamberlain for the miniseries

SHOGUN.

Yet

perhaps the most beloved is Amsel's portrait of Lucille

Ball, done for the magazine's July 6th, 1974 issue honoring

the comedienne's retirement from series television.

"I

did not want the portrait to be of Lucy Ricardo," Amsel

explained, "but I didn't want a modern-day Lucy Carter

either. I wanted it to have the same timeless sense

of glamour that Lucy herself has. She is, after all,

a former Goldwyn Girl. I hoped to capture the essence

of all this." Amsel's

work so impressed Ms. Ball that the artwork was later

prominently featured in the opening credits of a two-hour

television tribute, CBS Salutes Lucy: The First 25

Years.

Years

later, representations of Amsel's covers were placed

on exhibit at the Museum of Television and Radio in

Beverly Hills, commemorating TV Guide's fortieth

anniversary.

|

For

this opulent cover featuring Shogun, Amsel

took inspiration from the bold lines and vivid

colors of Japanese art. For the original painting,

he employed actual gold leaf on the clouds in

the background. (5)

|

Perhaps the most beloved of all his TV Guide

covers, Amsel's illustration of Lucille Ball honored

her overall "timeless sense of glamour"

rather than referencing a specific period. (5) |

THE

1980's

The

1980's marked a dramatic change in movie marketing campaigns,

with more and more employing photographs in favor of

illustrations. Movie poster artists now faced a narrower

field in which to compete, often limited to science

fiction, fantasy, and adventure films. The old masters

like Bob Peak -- whose bold, striking campaigns for

CAMELOT, STAR TREK, SUPERMAN, and APOCALYPSE NOW helped

redefine the very nature of movie poster art -- seemed

increasingly dated in their style, and had to make way

for a new generation of artists (notably Drew Struzan).

|

TV

Guide: Oct. 26-Nov. 1, 1985

(4)

The final work of art completed by Richard Amsel.

He died less than three weeks later, on Nov. 17,

1985. He was 37 years old.

|

Yet

Amsel remained productive, his trademark signature becoming

a widely recognizable fixture on further magazine covers

and movie posters, including such high profile, "event"

films as the colorful, campy FLASH GORDON, the elaborate

fantasy THE DARK CRYSTAL, and - of course - that action/adventure

film with a grandstanding name, RAIDERS OF THE LOST

ARK.

Amsel's

output garnered numerous awards, from the New York and

Los Angeles Society of Illustrators, a Grammy Award,

a Golden Key Award from The Hollywood Reporter, and

citations from the Philadelphia Art Director's Club.

His

last film poster was for MAD MAX BEYOND THUNDERDOME,

the third of George Miller's apocalyptic action movies

with Mel Gibson. His final completed artwork was for

an issue of TV Guide, featuring news anchors

Tom Brokaw, Peter Jennings and Dan Rather.

GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Amsel

died less than three weeks later, on November 17, 1985.

When

he fell ill, he was to have done the poster for the

ROMANCING THE STONE sequel, THE JEWEL OF THE NILE.

It's

been over two decades since Amsel's passing, and in

that time we've also said farewells to Bob Peak, Birney

Lettick, and John Alvin. (Alvin died of a heart attack

hours after this article was completed.) Peak's

sons, including artist Matthew Joseph, maintain

an online archive of their late father's work, and are

currently developing a book of his movie poster illustrations.

Alvin

and Struzan also have their

own respective websites, with the latter -- now the

leading figure among today's successful poster artists

-- having two extensive books already published chronicling

his career and work.

Yet

what of Amsel's legacy? While his art continues to amaze

and inspire, little has been said about the man himself.

I figured surely someone, somewhere in the world was

willing and able to speak for him.

Thankfully,

I was right.

In

researching this article, I came across some rare sketches

Amsel did in preparation for his RAIDERS posters. Having

never seen them before, I asked their owner how she

came to acquire them. Thus began a conversation that

led me to many of the answers I'd been searching for.

PERSONAL

REMEMBRANCES

Dorian

Hannaway is the director of late night programming at

CBS Entertainment. For years she has been the champion

of Amsel's work, fighting to get his name better recognized.

She also owns many of Amsel's original pieces. But to

call her a collector is inaccurate, for Hannaway's interest

was -- and remains -- a very, very personal one.

She

first met Richard Amsel in 1974, and the two struck

up a close friendship that lasted until his death. Perhaps

it lasts still, for while we discussed the artist at

length, Hannaway often tenderly referred to him as "My

Richard." It was clear to me that she is still wounded

by his absence.

|

TV

Guide: Jan. 27, 1979 (11)

Amsel's portrait of Katherine Hepburn is one of

my personal favorites.

|

"No

one, no one ever worked as hard as Richard," she said,

almost forcefully, in our first phone conversation.

Her knowledge led me to better appreciate the man, as

well as the artist I'd idolized. Hannaway, in fact,

conducted one of the few known recorded interviews with

Amsel, a profile of the artist for Emerald City,

a cable access show. Made in 1978, Amsel described his

work on the poster for the motion picture DEATH ON THE

NILE.

Among

their circle of friends were Jerry Alten, the art director

of TV Guide, and artist David Edward Byrd.

Byrd

is celebrated for his work featuring Jimi Hendrix, The

Who and their rock opera TOMMY, the commemorative poster

for Woodstock, and countless Broadway and Off-Broadway

shows. (His poster for GODSPELL is especially famous.)

He, too, was eager to share his recollections of the

late artist.

Amsel,

I would learn, was someone who was warm, gracious, and

full of life -- a handsome young man, stunningly gifted,

who surrounded himself with good friends, and was receptive

to and reciprocating in his friendships. But he was

also a complex man who, as is the case with many artists,

clung to his privacy and kept a great deal to himself.

"Richard

was an odd man," Byrd said, his tone far more affectionate

than in any way critical. "I called him the

savant. He was this genius, but had trouble negotiating

life in a bad way. He had no taste in clothes, but his

taste in art was impeccable. ... He wore the same outfit

everyday: a plaid shirt and bluejeans. I asked him if

he wore the same things all the time, or just had a

thousand copies of them! ... (Yet) he was vain in the

way he looked. He was very handsome, but he would never

wear his glasses -- he didn't like the way they looked

on him! So he couldn't see, he was almost blind!"

I

asked Byrd if he considered Amsel something of a social

misfit. He agreed, believing the description accurate.

He added in an email:

Richard

and I got on very well. We loved to talk with each

other about everything -- sometimes we would be

on the phone for five hours -- art history, artists,

technique, boyfriends, 3-strip technicolor, gossip,

pop culture, drugs, Nathalie Kalmus, Pete Smith,

pencils, Earl 'The Pearl' Moran, Film Noir, etc.,

etc...

I

went to California for the first time with Richard

and Dori -- Richard and I had just delivered TV

Guide covers to Jerry Alten the day before (John

Travolta by Amsel and Robert Conrad by myself).

We made a lot of Super-8 movies together. I was

Richard's date at the big TV Guide banquet at the

National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. It

honored both the subjects and their artists. I remember

we were at the table with Julia Child and Henry

Kissinger. We stayed in a seedy hooker hotel not

far from the event. We made a long movie about that

trip, which is pretty amusing!

In

describing Amsel's personality, both friends emphasized

the artist's sharp, droll style of humor. "He was very

silly, very funny," Hannaway said. "No one

had a sense of humor like he had." Byrd laughed, "He

had no social skills, but he had a stringent wit."

In

addition to his drawing abilities, Hannaway said that

Amsel was quite the skilled photographer. Working with

the late gay activist and writer Vito Russo (co-founder

of GLAAD and author of The Celluloid Closet),

Amsel contributed photographs to articles published

in The Advocate magazine.

SCHOOL

DAYS

After

this article was originally published, I was contacted

by other people willing to share some of their personal

recollections of Richard Amsel. Among them was one of

his classmates at the Philadelphia College of Art, Rhonda

W. Gross. Even in those early school days, Amsel's abilities

-- as it had been with J.C. Leyendecker -- were easily

apparent. Gross wrote in an email:

It

was obvious from the first weeks that he was a special

person, a generous spirit and worth watching. It

was an amazing class, that group from 1965 to 1969.

Many of us went on to become teachers as well as

practicing artists. Richard was so advanced that

many of our professors were intimidated by him.

They need not have been, as he was a gentle soul

who was generous with his methods and techniques.

I was a rapt observer, believe me. ...

Richard

was so amazingly ahead of the rest of us in so many

ways. His technique was fearless experimentation

with materials and techniques that we would wonder

how the art projects were going to work. Somehow,

they always did and we expanded our knowledge base

by watching him, sometimes to the consternation

of our professors.

Through the years I would see examples of his work

in the commercial art sector, and I was personally

honored to have known such a talented person.

TAKING

NEW YORK BY STORM...IN A TINY APARTMENT WITHOUT AN EASEL.

Another

person who contacted me was Michael Danahy, who met

Amsel in 1971 shortly after moving out to New York from

L.A. Both

men were only in their early twenties at the time, but

by even then, Danahy was amazed at Amsel's talent and

reputation.

"We

met at upper east side bar," Danahy said, noting

that Amsel didn't like to travel to the other side of

the city. "I think he thought it was beneath him,"

he laughed.

Yet

Amsel's own living accomodations back then could hardly

be deemed extravagant. They definitely weren't spacious.

"It

was smaller than most motel rooms," David Byrd

chuckled, remembering Amsel's Manhattan pad. "It

was maybe 400 square feet ... it had a tiny kitchenette.

I could probably do a drawing of what it looked like.

... He had an apartment in a luxe door-man high-rise

on the Upper East Side. ... Even when he moved out to

L.A., he always had to have a doorman!"

Dorian

Hannaway recalled how Amsel owned his own prints of

several classic Disney animated films, and would invite

people over to watch them. "He had a little one bedroom

apartment up on East 83rd Street, and would project

CINDERELLA on the wall."

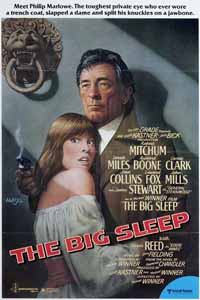

|

The

Big Sleep

(3)

1978

Watercolor, acrylic, colored pencils, airbrush

on board

22 7/8 x 16 in.

|

"Richard

kept all his art supplies in a cardboard grocery box

under the bed," David Byrd said. "His bed

was like a narrow cot that could

hold one person barely. Next to that was a 35mm projector

for his vast collection of 3-strip Technicolor prints

of everything worth seeing in that medium, from GONE

WITH THE WIND to COBRA WOMAN. He had a hole cut in the

wall of the bedroom so he could project the films on

the opposite living room wall. We had movie nights at

least twice a month, it seems."

The

sparse living arrangements remain vividly within Michael

Danahy's mind. "Richard lived on those stawberry

pop tarts," he said. "He never left his apartment,

especially when he was working. Everything was disorganized.

He had this little bedroom off to the left, and always

hid his paintings whenever guests came over."

This

latter fact, Danahy explained, hinted at the artist's

extreme privacy whenever his work was concerned. "He

was really hesistant to show anything until it was in

the form in which it was intended. He'd never let anybody

watch him paint."

That

is, almost never -- for Danahy recalls one occasion

when he had the rare opportunity to see his friend at

work. "I had to crash at his place one night because

I couldn't get home. Richard had a deadline. ... He

was always late, always disorganized, always started

the night before, always up all night, sitting on his

very 70s sofa with the canvas balanced on his knees..."

"His

knees?" I asked, not quite believing

I'd heard Danahy right.

I

had. Such a revelation filled me with creative shock

and awe. It

seems unthinkable that Amsel, who, having already established

himself with several major motion picture campaigns,

not only lived within such a tiny space...but was an

artist without an easel.

David

Byrd wrote:

Probably

the most amazing thing that people do not know about

Richard was his working habits. Richard worked on

his little glass dining table with the cardboard

box of Prisma Pencils, frisket, etc., on the floor

beside him. He never allowed anyone to see him work.

He was truly a 'savant' in that he could create

a gorgeous piece almost anywhere. ...

He came to my loft very often. I had a 5000 square

foot place in Chelsea, right off 5th Avenue at 17th.

He often shot photos for his jobs at my loft. For

instance, with THE BIG SLEEP, I stood in for Robert

Mitchum and my assistant, Amy, was Candy Clark.

THE DIVINE MISS M

|

The

Divine Miss M

(2)

1972

Watercolor, acrylic and colored pencils

14 x 14 1/2 in.

|

Michael

Danahy described how Amsel's creative influences were

often a mesh of art, personalities, and pop culture.

"Richard's most favorite subjects were famous women

and iconic gay characters. He was fascinated by them.

… He did the Bette Midler portrait because he wanted

to meet her. … He was courting her, but she was also

courting him."

That

courtship, as Danahy described it, began while Midler

was at the start of her career, making a name for herself

by performing in nightclubs and to packed audiences

at gay bathhouses (the latter earning her more cheerful,

endearing renown than sordid infamy).

"I

took him (Richard) to see Midler perform at Carnegie

Hall," Danahy said. "She was incredible … then we all

went to a party afterwards and everyone was on drugs.

But Bette Midler wouldn't even smoke a joint, when all

the rest of us did! … They were crazy times."

It

was Barry Manilow who introduced Midler to Richard Amsel,

and, their courtship sealed, the artist set off to do

the cover of Midler's debut album. That proved to be

a watershed moment in Amsel's career, and Danahy managed

to witness it firsthand.

He

recalled his curiosity over how the final portrait was

going to look: "I asked him what the cover was going

to look like, but Richard was still working on it and

didn't want to show me. Instead he grabbed a napkin

and drew Bette Midler's face. And that was it, her face

was immediately captured down on that sketch."

Amsel

and Manilow were good friends, Danahy said, but there

was a strained moment between them when Manilow, by

then readying an album of his own, asked Amsel to do

the cover -- and was denied. "Manilow was really upset

over that," Danahy said, and explained how Amsel, because

he was always working, had times when he needed to be

selective about the projects he worked on.

EVER

THE STRUGGLING ARTIST

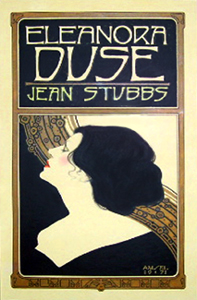

|

Elenora

Duse

1971

Size and medium unknown.

|

Danahy

added: "Richard struggled a lot (back then), and would

put things off because -- and I know this sounds strange

-- because he felt he worked best doing everything all

at once. I ran into him one time and he was stressed

out about finishing a project. I asked him, 'Why aren't

you working on it now?' and he said, 'I just can't work

that way… I need to wait.'"

And

however lucrative Amsel's commissions may have been,

Danahy tellingly added that Amsel's head for financial

matters was similarly remiss. "Richard had an agent

and worked with Society of illustrators in New York,"

he said. "He'd make around $5000 a poster in the early

seventies. ... that was a hell of a lot of money in

those days. … But he spent money as quickly as he earned

it. … It's not that he was deliberately indulgent or

extravagant, he just could never hold on to his money."

Danahy

recounted an oddly humorous tale regarding a Barbra

Streisand portrait Amsel had painted in the style of

Gustav Klimt -- which was stolen while on exhibit at

the Philadelphia Art College. "The painting was gorgeous,"

he said. "I was shocked when I found out, and I asked

Richard if he was okay. I thought he'd be so upset,

but instead he laughed ... he was compensated $147,000,

and was thrilled! He told me, 'God, I hope they don't

find it, otherwise I might have to give all that money

back!'"

Danahy

admits that he lost touch with Amsel after 1973, but

values the close friendship they had during their few

years together. Now a film producer in Los Angeles,

Danahy

is also a proud owner of one of Amsel's original pieces

- a paperback book cover illustration for Eleanora

Duse, given to Danahy by the artist himself.

"He

was planning to throw it out to make more room in his

apartment," Danahy said, "so I asked him if I could

have it." Ever the bargain hunter for films to show

on his beloved movie nights, Amsel offered Danahy the

painting in exchange for some of his Disney reels. Today,

Eleanora Duse remains framed and on display within

Danahy's home.

THE ARTIST'S TECHNIQUE

|

Amsel's

painting for THE SHOOTIST, John Wayne's final

film, incorporated gold paint on the background

even though its shimmering effect couldn't be

reproduced on the posters. (2)

|

I

asked Dorian Hannaway about Amsel's painting technique,

for however familiar I may have been with the artist's

work, I'd yet to see many images chronicling his creative

process. It's one thing to see a finished piece, but

quite another to see how it all started.

Amsel

worked with all sorts of mediums. He frequently used

thin glazes of acrylic, like washes of watercolor, and

then applied colored pencils and pastels. He'd then

go back and forth, combining them little by little,

layer upon layer, until the piece was completed to his

satisfaction.

Sometimes

his methods were more exotic. For his illustration on

THE SHOOTIST, Amsel used gold paint to accentuate the

background, even though printing limitations prevented

its shimmering effect from being accurately reproduced.

For McCABE AND MRS. MILLER, the artist's "canvas" was

an actual piece of wood, keeping in the style of the

period western.

PRESERVING AMSEL'S LEGACY

When

I first met with Dorian Hannaway at CBS, my eyes lit

up upon entering her office. Amsel's posters dominate

the room - each one tastefully placed, beautifully framed.

There was also an original piece - a curious, three-sided

block of wood Amsel painted as part of a promo for the

film THE LAST OF SHEILA. I held the thing in my hands

and was stunned by the level of detail -- so good that

it was as if Amsel had painted it five times its actual

size, then glued shrunken photographs of the artwork

to each side. The greedy little kid in me was tempted

to steal it.

Hannaway

took out a large, handmade three-ringed binder, an impressive

thing several inches thick. She opened it to reveal

a chronological archive of Amsel's work. The book itself

seemed to be a labor of love -- Hannaway's prized possession,

her own little Holy Grail or Ark of the Covenant. I

could hardly blame her, for as we sat on the couch flipping

through the pages I was transfixed by the images I saw.

|

Poster

for RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK's American release

in 1981. George Lucas owns the original Amsel

art, while Steven Spielberg owns the re-release

illustration.

|

There

were pages, many pages, of Xeroxed pencil sketches,

of color photocopies, of art comps and studies. Some

were simple thumbnail sketches - tiny things Amsel loosely

whipped up on the fly; seeing them was like stepping

through a doorway to his mind. Other colored sketches

were quite detailed - so good, in fact, that they could

have easily made for impressive final designs.

There

was a copy of a GQ cover Amsel

painted in the style of Gustav Klimt, a glorious thing

the Austrian might have done himself. There were sketches

of Richard Chamberlain in samurai garb, studies for

the TV Guide SHOGUN issue; Hannaway shared that

Amsel used actual gold leaf for the final illustration.

Most

of this I'd never seen before in any form. They included

designs for such films as CUBA, KRULL, SAHARA, and GREYSTOKE

-- poster campaigns that Amsel didn't get. Even

the most talented runners can still lose a race, and

I realized that however much success he enjoyed, Amsel

still had to fight like hell to get each job.

Byrd

later confirmed my feelings, adding: "Richard never

did art for his own pleasure. He needed to be paid."

Hannaway

showed me Amsel's RAIDERS comps. The

first sketch was a quick pencil rough - a tiny image

of Harrison Ford, whip in hand, with small circles standing

in for what two or three characters would be. Yet even

in this early form, Amsel's layout for the first Indiana

Jones poster was almost exactly identical to the final

product.

"That

was it," Hannaway said. "Richard came up with it, just

that way. He drew Harrison Ford, and that's how it stayed

for the final poster."

The next page revealed Amsel's color composition for

the design, a second step between the tiny rough sketch

and the large final illustration. It was detailed, drawn

very much like the polished portrait, but with bolder

lines and more vivid red and orange colors. Both beautiful

and commanding, it reminded me of Bob Peak's intense

portrait of Marlon Brando, done for his eye-catching

APOCALYPSE NOW poster.

Hannaway

owns this original comp, but getting it was a task worthy

of Indiana Jones; the passage of years, and collectors'

high demand for Amsel's work, have made the artist's

original pieces very, very hard to come by.

A

TRAGIC LOSS

I

asked Hannaway if Richard's death was sudden. It was.

"He

found out he had AIDS in September, and he was dead

by late November," Hannaway said softly. By then the

disease had ravaged many in the gay community, and few

medical advancements had been made in treating those

afflicted. Rock Hudson's death happened just the month

before.

In

1985, soon after Amsel moved out to Los Angeles, Byrd

grew increasingly alarmed by his appearance. "I'd

never seen him look so thin," Byrd said. "He

was also chain smoking, and I'd never seen him smoke

before."

He

recalled their last conversation. "He said he was

going to New York and needed an operation. Then,"

Byrd sighed, "he was dead."

Michael

Danahy, too, was shocked by the news of his old friend's

death, and expressed his profound sadness over the loss

of nearly an entire generation of gifted artists and

performers to AIDS. Many other friends from his days

in New York were taken by the disease, including celebrated

illustrator George Stavrinos, with whom Danahy was especially

close. Danahy's testimony not only provides us with

a rare glimpse into Amsel's early career, but serves

as a stark reminder of the profound impact -- and tragedy

-- of the epidemic.

A

FAMILY REMEMBERS

It

would be inappropriate to ever consider this tribute

complete without hearing from members of Amsel's family,

so imagine my reaction to the following email (excerpted),

which I received in early September of 2008:

This

is Michael Amsel, Richard's brother. I just wanted

to commend you on your extraordinary web site about

my brother. What a marvelous tribute! You captured

everything about him, so accurate, so moving. No

one was more prolific or harder working than my

brother. He accomplished more in 37 years than anyone

I have ever met. He would have absolutely loved

the web site.

Anyway

… I just want to thank you again for your marvelous

work. It really brings a tear to my eye. What a

great way to keep Richard's memory alive!

Michael generously accepted my request for a phone interview,

which was followed some weeks later by a separate call

from his twin sister, Marsha Lee. Throughout

our conversations, it was clear how much they both still

held their older brother in loving esteem.

|

Photo

of Richard Amsel. (2)

|

"The

first word that comes to my mind when I think of Richard

is prolific," Michael said. "To do

what he did in 37 years is amazing. To have potential

is one thing, but to really push yourself and realize

it is another."

I

asked Michael about their childhood, and if Richard's

creative prowess was evident at an early age. "We were

very different as kids. I was always out playing, while

he was always in our room at his desk," he told me.

"When we were about six or seven, we all did those paint-by-numbers

books, and Richard's were, like, PERFECT. You'd look

at it and couldn't believe it was a paint-by-numbers.

There were no lines, it all looked like a real painting.

That showed the kind of work he was capable of."

He

described how Richard's interests and abilities intensified

through his teens. "Even when he was in high school,

he just worked endlessly," he said. "Some of his early

stuff is really amazing, and clearly foreshadowed his

greatness. … It's incredible how true Richard's drawings

were to the people in them."

Marsha

Lee described a little bit about their background. The

Amsel siblings grew up in Lynwood, Pennsylvania, and

their father ran a small clothing and toy shop in the

nearby town of Ardmore. "Mom would give Richard

these model toys and paints from the store, and he'd

be fascinated with them," she said. "I think

she was the one who gave him his very first set of paints.

"We

were a lot alike. ... People say that Richard and I

had similar expressions, in the ways we'd react,"

Marsha said. "Sometimes, back when we were kids,

after our parents would leave the house, Richard would

take Mom's makeup and do up my face. ... We both loved

glamour!"

Michael

told a story about a young girl Richard had been best

friends with during childhood. She lived across the

street from them, and was an aspiring artist herself.

When they graduated, it was she -- not Amsel

-- who won the coveted art scholarship. "It was disappointing

for him," Michael said. "It wasn't easy for our parents,

either, with all these kids in the house and going off

to college."

Ironically,

while Amsel went on to worldwide fame, Michael believes

that their childhood neighbor never established an art

career of her own.

Michael's

own son, Joseph Richard Amsel, now attends his late

uncle's almer mater, Philadelphia's University of the

Arts. "Joseph has aspirations of someday working in

film," Michael said, "and clearly has been inspired

by Richard, who he knows only from the pictures at our

home and exhibitions he has attended. Today, he has

his first illustration class at University of the Arts

… and off he goes. What were the odds of him following

Richard there?"

In

what is perhaps a bittersweet victory of sorts, Joseph

was also awarded the very same art scholarship that

had eluded Richard back when he was his nephew's age.

"I like to think of it as fate," Michael says proudly.

"It runs in the family."

He

added, "Fate, it seems, brought me to discover your

site at what was a very emotional time for me. My wife

and I just returned from taking Joseph … to Philadelphia.

... It just warms my heart to no end to see him there

because I remember how Richard came of age, with his

drawing boards and paint supplies jammed into the trunk

of a red Corvair, and his endless hours of work at home,

when he returned from classes. …

"One

of the professors I met at University of the Arts freshman

orientation last week remembered Richard coming back

to the school in his late twenties, and giving a speech.

'He was treated like a rock star that day,' the professor

said. 'The students were in awe.'"

While

Michael himself was at college, a surreal moment occurred

one day when he walked through the streets of Columbus

... and saw a familiar looking poster at a nearby movie

theater.

|

Amsel's winning design for Fox's HELLO DOLLY campaign,

1969. (The final poster can be seen

here.)

|

"I

still remember (Richard) painting the HELLO DOLLY illustration

in our room and seeing it, two years later, at a movie

house in Columbus, Ohio, when I was a freshman at Ohio

State University. It has been a lifetime inspiration

for me. It made me realize what a small world we live

in. … Dreams can become real … It really blew my mind

when I saw it.

Over

the years, Michael and Richard remained in contact,

but saw less and less of each other. While Richard's

career in art flourished, his younger brother embarked

on a career in journalism. "There was mutual admiration

between us," Michael said. "I loved journalism, and

he loved art."

Michael

remembers a time later on, after moving out to New Jersey,

that he went inside a convenience store and saw one

of Richard's TV Guide covers on sale. "He must

have done about forty of those covers -- my God, how

did he churn them out so fast? -- but seeing them, it

was through that, you knew that he was well. It was

like his way of telling us, 'I'm alright, I'm doing

okay...'"

Alas,

Michael Amsel admits that they did not have much communication

towards the end. They reunited briefly for their grandfather's

funeral -- "It was weird, with all that grief, and after

all those years," he said -- but when Richard's illness

began to get the better of him, Michael said that he

and his family were largely left in the dark.

In

the time leading up to Richard's death, Michael was

facing a health crisis of his own -- one that left both

him and his parents occupied. "I was in a hospital in

New Jersey about the same time Richard was (in another

hospital). I had a couple of broken disks, and was having

a laminectomy. I was out of work for five months, stuck

in bed. … My parents came out to visit and helped me,

but they hardly knew about Richard's situation."

Then,

late one night, came the terrible, devastating news:

Michael's mother called to tell him that Richard was

dead.

It

was as if the ground had fallen out from beneath their

feet. A shock. A tragedy. Something no parent should

ever have to hear, and no brother would ever wish to

imagine.

It

was Michael who delivered Richard's

eulogy, but it was a number of years before he truly

faced dealing with the psychological scars of love and

loss left in the wake of his brother's passing.

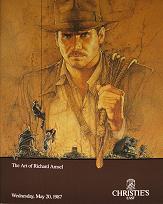

|

In

1987, many of Amsel's remaining originals were

auctioned off by Christie's.

|

"It

wasn't until the last eight to ten years that I really

came to terms with it," Michael said, adding that through

his work as a journalist -- by covering stories and

talking to people about death -- he finally managed

to find a form of catharsis of his own.

The

pain surrounding Richard Amsel's passing was further

complicated by the state of his unfinished financial

affairs. This led to an auction in 1987, sponsored by

Christie's, whereby a large portion of the artist's

work was put up for public sale.

Michael

sighs as he remembers it all: "The Christie's auction

… I guess it's such a mystery. So much of his work …

so unfortunate." Nevertheless, he tries his best to

put it in perspective with his brother's creative spirit.

"Richard was the quintessential artist. He was so focused

on his work that all the other things in his life just

fell by the wayside. That was the result of the genius

of the artist."

Michael

and Marsha are delighted by the enduring popularity

of Richard's work, as well as the inspiration artists

and illustrators the world over continue to take from

it. Their support of (and contribution to) this website

mean the world to me.

"Thanks

for everything you've done for Richard," Michael told

me. "You're part of Richard's renaissance."

AN

APPRECIATION

I've

always admired Richard Amsel's work, and after talking

to those who knew him, I can now admire the man. Certainly

I'd value the opportunity to hear from others who knew

him; I'd be glad to include their comments here.

David

Edward Byrd reflected in an email:

Richard

was my art hero, a true A-Team player. I always

considered myself on the B-Team, so to speak, a

modest talent with a modest success. And, oddly,

Richard Amsel is the only illustrator I have known

socially, except for my first student at Pratt Institute,

Frank Verlizzo, who became a great Broadway Poster

artist....

I

am forever in awe of his (Richard's) ability to

draw in any style. In even the tiniest sketch, the

likeness of the person is there.

Amsel's

death may have been tragic, but his life assuredly was

not. In spite of his absence, let us simply give thanks

for those magical things about him that were left to

us...

The

work.

And

what great work it is! It is silent, yet speaks volumes.

It is clever and romantic, sometimes tacky and fanciful.

It is often striking and it is always gorgeous.

Take

a look at some of the images here. Study them; imagine

how they came to be before the use of colored

pixels and stylus pens. These are not just polished

illustrations, they are true works of art...the labors

of a true artist. They've excited moviegoers and inspired

new generations of artists and illustrators. I proudly

consider myself among them.

Looking

back on his days with Richard Amsel, Byrd said, "We

lived in a time that was more interesting." The

sentiment doesn't surprise me, for interesting times,

I suspect, are largely the result of being in the company

of interesting people.

Here's

to you, Richard, wherever you may be.

Copyright

(c) 2008, 2011 Adam McDaniel.

|

|

A

few days after our phone conversation, I received

an envelope in the mail from Michael Amsel. I

opened it to find an undated sketch that his brother

had done of Marilyn Monroe. I always dreamed of

one day having a Richard Amsel original, but never

thought it'd ever come to pass. Michael proved

me wrong. Dreams, it seems, can indeed come true.

|

|